Red Sea Shipping Crisis Upsets Global Trade

2024-01-111175 view

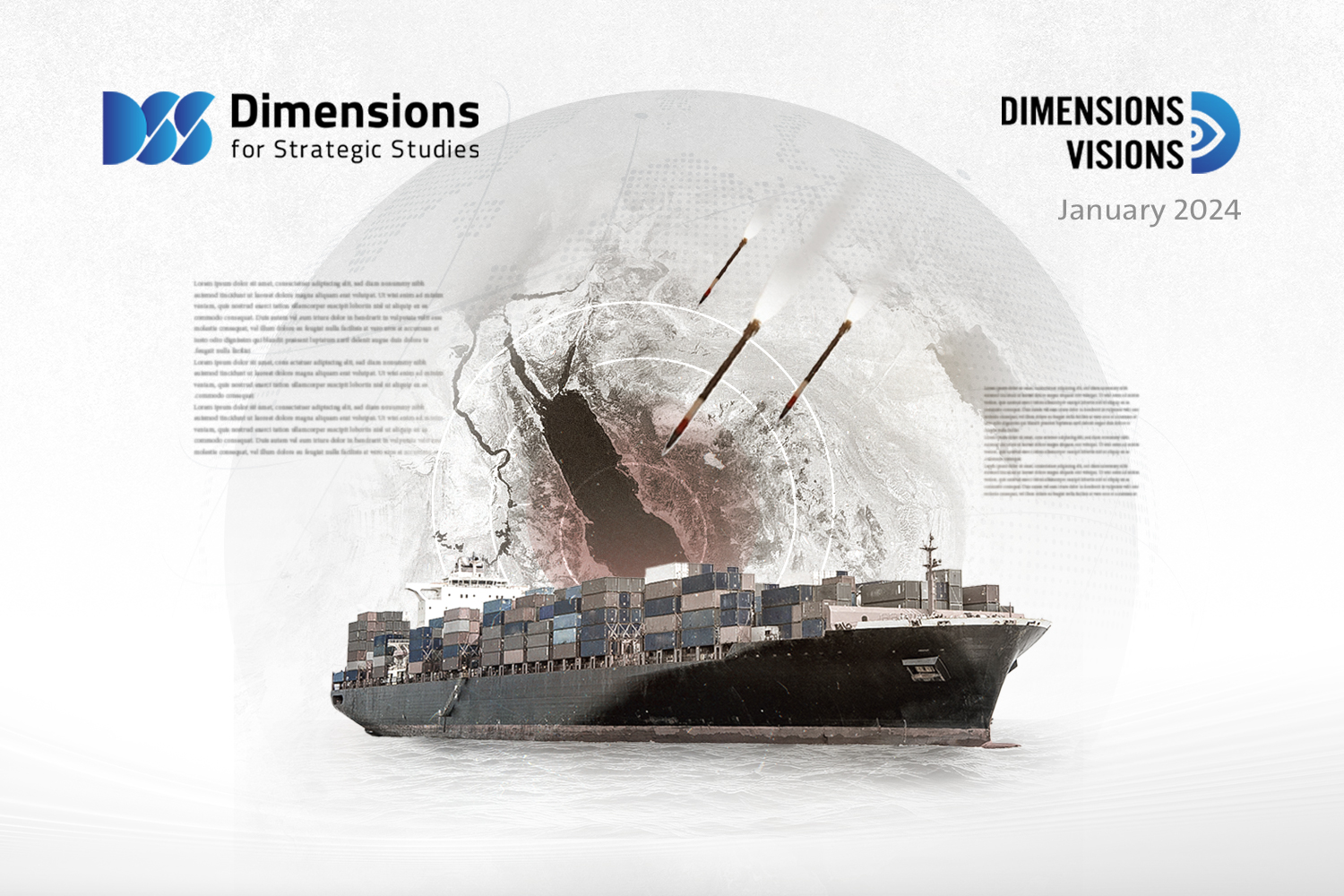

The Red Sea is a vital artery for international navigation, accounting for more than 10% of global maritime traffic. Its significance as a conduit for international commerce also bestows substantial benefits on several countries – notably Egypt, which earns transit fees from ships passing through the Suez Canal, while countries like Jordan and Israel rely on the route for both imports and exports.

Pressure Point

Attacks by Yemen’s Huthi rebels on commercial ships in the Bab al-Mandeb strait since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza last December were not without precedent. Over the course of 2022, the group reportedly attacked more than a hundred ships in the area. However, the group has significantly stepped up its attacks on shipping in the wake of the Gaza conflict, targeting vessels from multiple companies and prompting major shipping firms to reroute their ships.

The United States and its allies have launched a military operation to halt the Huthi attacks and secure maritime traffic through the Red Sea. However, this operation will ramp up tensions and has fueled fears of a broader regional war; cargo firms using the Red Sea route will continue to be on edge.

Obstructing trade in the Red Sea, the main sea route linking Asia and the Arabian Gulf with the Mediterranean, has two immediate impacts. Firstly, ships have to take a longer route, which means more operating days and greater costs. Secondly, the cost of insuring ships and the cargo they transport will be higher than ever due to the risk they may be targeted, whether in the Red Sea or elsewhere. Of course, these additional costs are borne not by merchants but are passed on to consumers, as reflected in spikes in the prices of imports. This means that the world faces higher prices for goods due to increased shipping costs.

Higher Shipping Costs

This situation is not entirely unprecedented. Shipping costs have been rising since early 2020 and the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. That crisis led to border closures and production shutdowns as well as preventing workers from traveling. Prices multiplied during the pandemic, to the point that some firms began monitoring their ships by satellite for fear of theft and piracy.

In the second quarter of 2021, the world breathed a sigh of relief as the coronavirus began to recede, hospitals and medical personnel became better able to treat patients and vaccination campaigns began to roll back coronavirus caseloads. Yet despite the health crisis receding, its actual economic effects were only starting to appear. Production capacity was no longer able to meet demand, shipping costs rose severalfold, and the price of oil began to rise again.

Although stimulus packages helped stimulate the world economy and saved a large number of companies from bankruptcy, they also created monetary burdens that needed to be addressed by raising interest rates, meaning higher borrowing costs for both companies and governments.

Then in early 2022, Russia sparked a new global crisis by invading Ukraine. Both countries are major global exporters of food commodities, and Russia is also a major source of energy with a key strategic role in European markets. Countries in Europe were therefore forced to import from more distant places to compensate for the shortfall in supply from Ukraine and Russia. They succeeding in managing the crisis, but at still incurred high prices as suppliers exploited demand and a supply crunch in Europe and elsewhere for food and energy. French President Emmanuel Macron thanked countries that helped the continent deal with the crisis, but complained that prices had once again risen sharply.

The “Al-Aqsa Flood” attack by Palestinian Hamas militants against Israel in October sparked a devastating war that has had a ripple effect across the region. One immediate effect was that ships moving through the Red Sea now faced the threat of attack by Huthi rebels in Yemen, prompting the creation of a Western military alliance aimed at protecting international shipping. The Red Sea crisis has in turn sent international shipping costs soaring.

Protectionism Trumps Free Trade

In 2020, governments opted for local and national solutions rather than international cooperation as the basis for resolving crises - even global ones, such as the spread of a virus across borders. States worldwide closed their borders and clung to their resources. Britain’s exit from the European Union has also strengthened this tendency, and talk grew of a new era in international trade, characterized by protectionism, in contrast to the free trade and simplification of customs procedures long promoted by the World Trade Organization.

In this context, transportation costs have ceased to be a secondary issue. Rather, the cost of shipping has risen to levels equivalent to the price of production itself, or sometimes even more, a phenomenon that could be labelled the “globalization of costs”. This implies that all countries have equal opportunities when it comes to production costs, and that being competitive depends not on producing the cheapest goods, but rather those of the highest quality. This is clearly demonstrated in some major economies, such as Turkey, where the costs of most commodities have risen not only due to the collapse of the country’s currency, but also due to the increase in the real costs of commodities.

The Huthi attacks, which have disrupted commercial traffic through the Red Sea, along with the response of world powers, are therefore situated in a general context of rising shipping costs, skyrocketing insurance premiums and stubbornly high energy prices.

The attacks are therefore simply the latest in a serious of crises affecting supply chains, but one that adds serious pressure to international trade and could mean that countries with surplus production become less competitive than ever before. Notably, this could affect China, whose imports were slightly up in 2023 but by less than had been forecast by local experts and Chinese officials dealing with international trade.

Indeed, China’s bilateral trade with some countries has actually declined on an annual basis, due to higher shipping costs. If these trends continue, they may mark the beginning of a new phase in which China will bear the brunt of the storm.

A Near-Term Negative Outlook

Several countries in the Red Sea region have already suffered direct losses due to the Huthi attacks, perhaps most prominently cash-strapped Egypt, which generates millions of dollars a day from the Suez Canal. Israel has also been directly affected by the crisis, as fewer ships are reaching its ports, whether for transit purposes or to deliver goods to and from Israel.

However, in the medium and longer term, the Huthi attacks bring a substantial new element to a string of successive crises in the international economy. This new context is characterized by high costs, which will cause certain countries to lose their comparative advantages.