Sovereign Debt Hangs over the Arab World

2024-07-082979 view

Argentina provides Arab governments with a sobering example of the hazards of public debt. The country has repeatedly defaulted on its loans, resulting in political unrest and repeated collapses in the value of the currency, plunging large numbers of citizens into poverty.

Successive governments have been forced to adopt economic programs dictated by foreign creditors seeking to safeguard their own interests, while state cost-cutting programs have included mass layoffs, resulting in unprecedented levels of unemployment.

Such a scenario is anathema to governments around the world. For Arab regimes, any foreign intervention sparked by a default would contrast sharply with the slogans of independence, sovereignty, and rejection of foreign interference on which these regimes base their legitimacy.

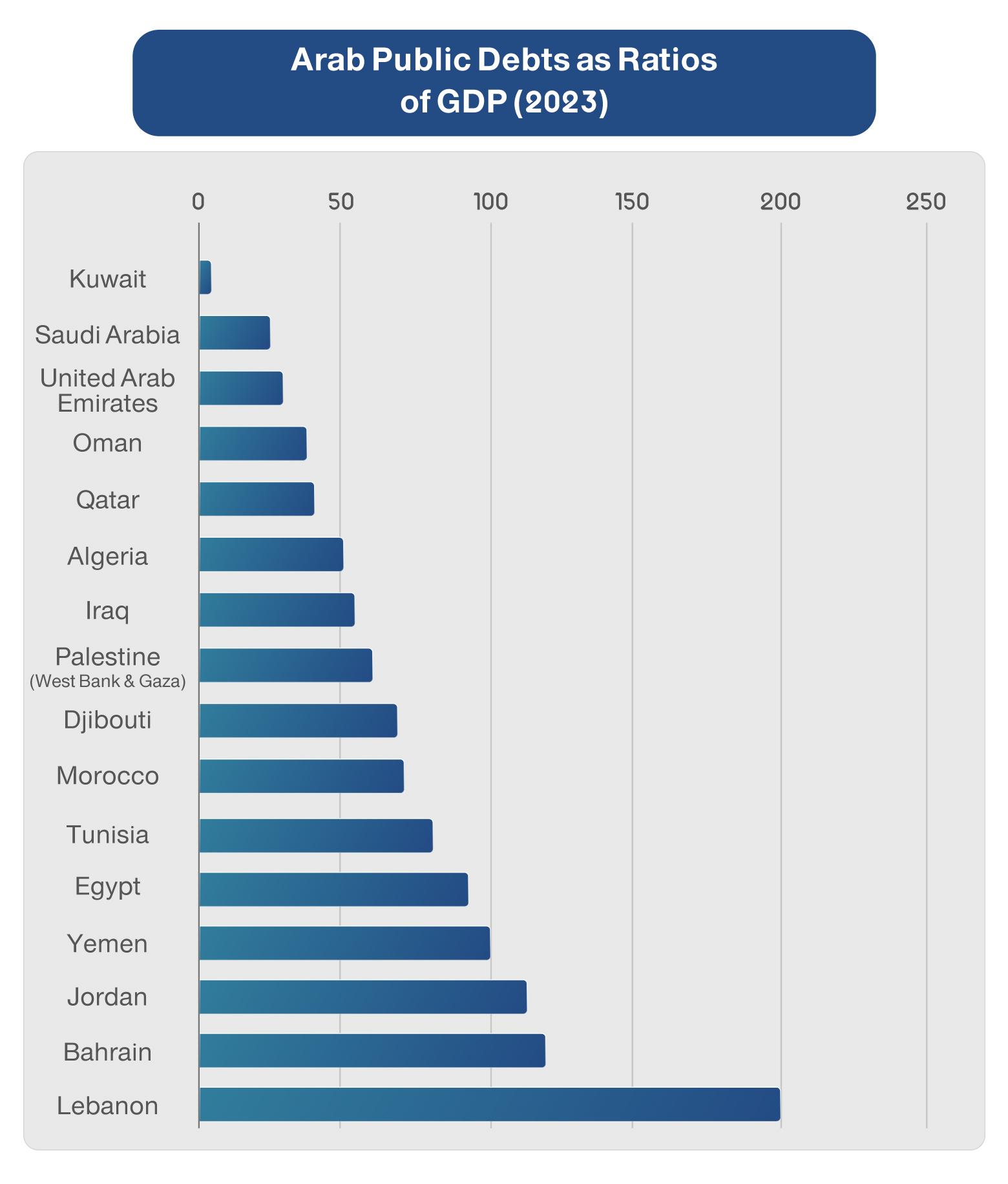

Lebanon is perhaps the region’s starkest example of the perils of sovereign indebtedness. In early 2020, the government announced it was unable to meet its repayment obligations, the first sovereign default in its history. Several years on, the country continues to struggle under grim economic conditions: rising prices, plunging foreign investment, persistent but as-yet unfulfilled calls to hold politicians accountable, appeals to foreign creditors, and stalled negotiations with potential donors.

Lebanon is not alone in facing collapse due to high public debts. Both Tunisia and Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous country, could face similar scenarios. Less stable countries such as Libya, Yemen, and Iraq also have crippling debts, although they are difficult to estimate due to the lack of reliable statistics or because of ongoing armed conflicts. Some richer countries such as Bahrain and Oman have faced, or continue to face, difficulties meeting public debt repayments. Indeed, most Arab states are facing the problem of spiraling sovereign debt (as a ratio of Gross Domestic Product or GDP).

One might argue that major world powers, including France, Britain and the United States, have high rates of public debt, both in absolute terms and relative to GDP. However, these countries’ economic conditions differ markedly from those of Arab countries, so the two models cannot be compared.

The main issue for Arab debtor nations is that they are struggling to meet interest payments and scheduled installments, for both political and economic reasons. The government of Lebanon has been effectively halted since 2022 and operates as a caretaker administration.

The country is also prone to disputes between political parties, each of whose interests conflicts with the interests of the country itself. All this is taking place under the specter of war, and as investments flow out of the country and the lira continues to plunge in value.

Elsewhere in the region, five Arab states—Palestine, Syria, Yemen, Yemen, Sudan, and Libya—are in various degrees of fragmentation. This both poses an obstacle to further borrowing and makes it hard for these countries to repay their debts without incurring high costs. The Syrian regime, for example, has resorted to paying its debts by selling assets to Iran.

Egypt, for its part, has undergone multiple political upheavals in the last 15 years. Its financial situation has forced it into a stringent, internationally imposed austerity program that some argue it will not be able to complete.

In general, non-oil-exporting Arab countries are facing a steep energy costs, difficulties in securing basic necessities—whose prices have risen dramatically in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and weak investment, further adding to the difficulty of repaying debts.

Lebanon is creaking under debt worth twice its GDP, and while the value of the former is rising due to interest and late payments, the latter is receding. Oil-rich Iraq has a debt ratio close to 60% of GDP and a below-average credit rating of B- (S&P) or CAA1 (Moody’s). Tunisia has an even lower credit rating than Iraq and Egypt, and is also at risk of default.

In summary, most Arab countries face debt-related issues, not due to their high levels of public debt per se, but due to problems over repayments and their timetables. During a period of low oil prices, even Kuwait—one of the richest countries in the Arab world—faced difficulties in meeting its debt payments. Since its public debt law expired in 2019, Kuwait has been discussing a new law, but despite more than five years of deliberations, it has yet to be adopted. This shows that sovereign debt causes issues even for rich countries—let alone poor ones.

Reforms and Rationalization

Political unrest, government perceptions of foreign debt and international institutions, high energy bills, elevated prices of key imported commodities, capital flight or hesitance on the part of foreign investors: all these factors mean that public debt threatens to become a major crisis for many states in the region.

However, several groups of factors could help governments meet their repayment obligations. Broadly, these fall under two categories: political factors and economic factors.

Political reforms to ruling regimes in debtor countries could raise the level of accountability, increasing transparency and government efficiency, and thus create both public pressure and official momentum towards paying off installments and fulfilling the state’s obligations.

When it comes to economic factors, implementing genuine programs of reform that contribute to reducing and rationalizing government spending, while reducing corruption, could have a major impact on states’ ability to repay their debts. Such programs could also help maximize the financial resources of debtor countries and thus improve their ability to repay.

Sadly, in the absence of such programs, the results can be little short of disastrous. Lebanon, which defaulted on its debts in early 2020, is a case in point. Today, Tunisia and Egypt are particularly close to defaulting on their debts and interest payments. Meanwhile countries such as Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, Sudan, and Palestine face even greater challenges, given their total dependence—or rather, the total dependence of their ruling elites—on their creditors. Syria is a case in point.

Arguably however, public debt is only one of an array of overlapping challenges facing Arab debtor states, which are also confronted with pressing political problems, armed conflicts and factional struggles.

In this context, Arab countries with high public debts can usefully be divided into three categories:

• Countries with large debts that also face more pressing problems, and need political reforms along with social stability in order to avoid total collapse. Examples include Sudan, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Palestine and Yemen.

• Countries whose indebtedness puts them at risk of default, with the potential to disrupt the functioning of the state and weaken its ability to perform its primary tasks. This is the case in Tunisia, Egypt and Djibouti, which are in dire need of real economic and political reforms in order to overcome these challenges.

• Countries with large debts, but whose better economic conditions mean they are less vulnerable to crises. This is the case of Bahrain and Oman, as they have sufficient resources to meet their obligations.

Indebtedness poses a double problem for Arab states. Firstly, sovereign debts require repayment of the original amount plus interest, which deprives citizens of resources they could have enjoyed had this debt been absent or at lower levels. Secondly, heavy indebtedness exposes the state to its creditors, raising the question of sovereignty, a highly sensitive topic for Arab ruling regimes.

Therefore, the main lesson to be learned from sovereign debt in the Arab world is that there is a fundamental need for reconciliation between the ruling powers and their peoples, through genuine political reforms and economic programs that serve the public interest.